A little over 25 years ago I went, as a student, to hear the painter Robert Motherwell give a revealingly honest and insightful talk about his past 25 years as an artist. I remember being impressed by his casual style and the humour with which he treated his exalted status.

It was also at about this time (1972) that I came across the recent image-based paintings of Phillip Guston, as he was in the process of treating the art world to his masterful self re-defining.

Both experiences were humbling in that I was 25 years old at the time and rather full of myself and of my place in the artistic universe. Little did I realize that life and a life in art was, to quote a French saying, “a long, slow river”.

Time along with experience has shown me that there is more to art than art and that life and its complexities make up the great braided web of content that one would have to call a life in art.

As a 12 year old immigrant to this country, and to California, I was left to my own devices in order to maneuver the amazing novelty of my new home. A combination of nostalgia, in-born curiosity, and benign outsider status gave me a sense of wonder about my place in the world. The fact that my reality spanned two cultures and (in my fantasy) two continents, trained me to recognize and make use of an over-active imagination.

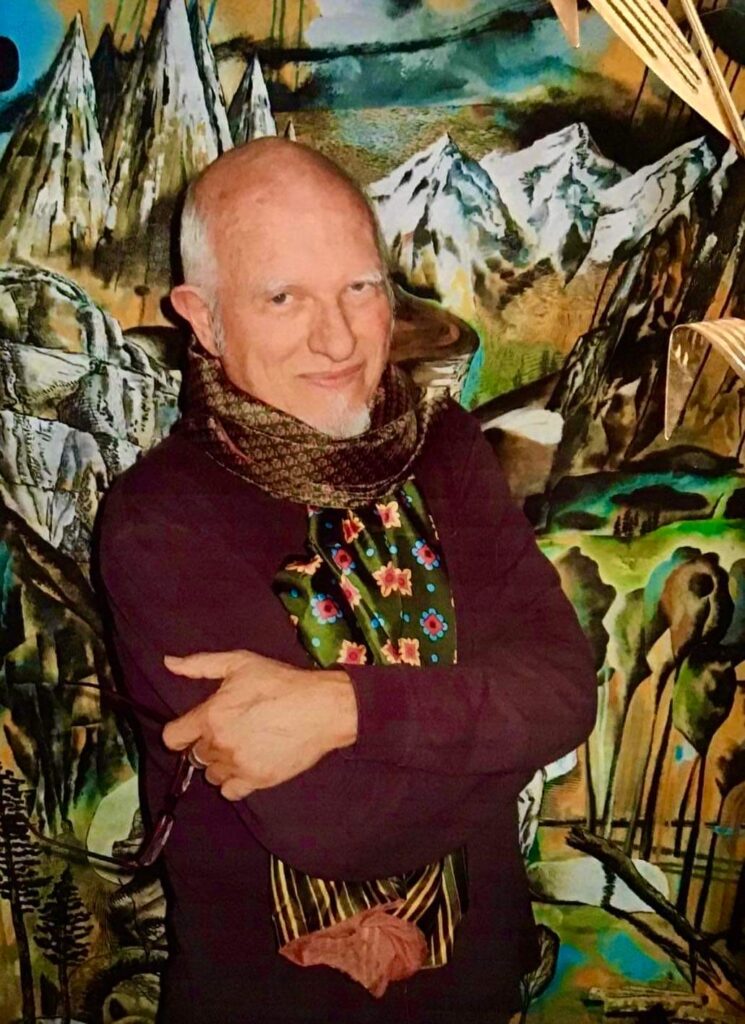

This has been the foundation of my work as a painter. Ever since my years at university, I have been continuously intrigued by the massive variety of cultural production to be found in the world. The fact that this production has spawned so many artistic disciplines as well as histories has given me, as a culturally motivated participant, a sense of belonging to a body greater and more far-ranging than myself or of any language, style, school, or issue.

My work speaks of an awareness of art’s potential and my inability, if not my unwillingness to be limited by a specific voice. It also attempts to acknowledge, evaluate, and satisfy my reactions to and interest in the constant flow of stimulation and information I/we are subjected to.*

* I speak of films, news events, clothing, chance encounters with odd fragmented juxtapositions in signage, images, gestures, which abound in the world. This would include not only the admiration I have for artists who figure in the Pantheon, but for those who have fallen through the cracks of history and culture: outsiders, solitary geniuses whom I have had the pleasure to “discover” (F.X. Messerschmidt, Leon Kossoff, Alfred Kubin, Florine Stettheimer, Euan Uglow, Clovis Trouille, Mario Sironi, Hercule Seghers, and so many others), and who have invoked in me the surprise and awe which history has a tendency to wear down.

Even though I pursue distinct themes through obsessive series of work, the results do not necessarily have a particular look, style or image. This occurs because of the wide range of sources, knowledge, and techniques I use in my vocabulary. The content, direction and interests of my lexicon expands continuously. Although this attitude has its detractors, especially when concerning the commercial viability of work associated with my (or any) name, it is an acceptable alternative to the production line: I have been there and it holds no further interest for me.

We are all seeking answers to questions that are as old as time, hoping to achieve some sense of clarity through our chosen means of inquiry. Most artists (painters, designers, musicians, writers, architects, etc…) are involved in a search for truth and meaning, and in finding approaches to address and communicate this elusive proposition. Even within the extreme stance of the nihilist lurks an idealist, a disappointed believer, a fallen romantic looking to achieve a sense of substance, strength and truthfulness.

These are the issues which I grapple with, a position wherein immediate answers are neither readily available nor promised. I have found a way, via my work, to continually stay conscious, which allows me to be in an evolving dialogue with the culture at large, Through my willingness to step back, move forward, turn around, or shift direction, the flow of my work and its long slow progression can remain fresh and surprising both to myself and to my viewer.